All:

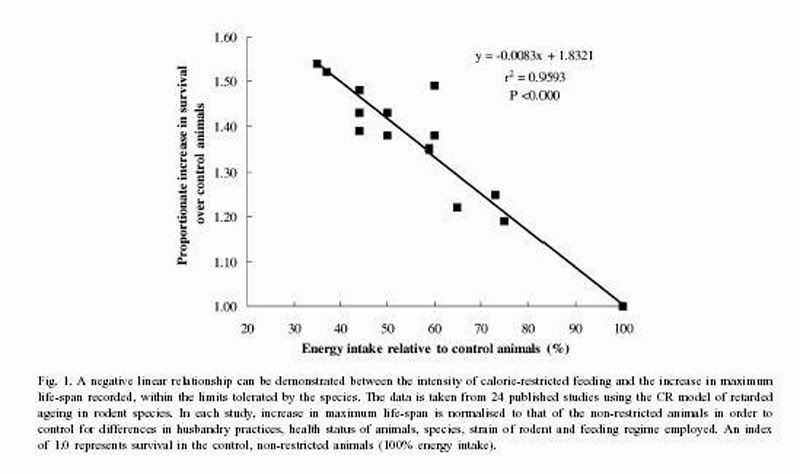

In recent posts, I've documented that alternate-day fasting (IF/EOD) without a concomitant reduction in Calories consumed fails to retard aging or extend lifespan in rodents. More recently, I reviewed evidence that compressed-window daily eating and alternate-day fasting does not provide the benefits of Calorie restriction in humans.

I was recently pointed to an old review ((4) -- published before the clear refutation in (7)) that tried to make the case that alternate-day fasting (= "intermittent fasting" (IF) = "Every Other Day feeding" (EOD)), without accompanying reductions in Calorie intake, would indeed provide the benefits of CR:

It was assumed for many years that the physiological responses to [CR and EOD] paradigms were due exclusively to a net decrease in energy intake. Recently, however, it was found that some species and strains of laboratory animals, when fed AL every other day, are capable of gorging so that their net weekly intake is not greatly decreased. Despite having only a small deficit in energy intake relative to control levels, however, these animals experience enhanced longevity and stress resistance is enhanced in comparison to AL controls as much in animals enduring daily restriction of diet. These observations warrant renewed interest in this paradigm and suggest that comparisons of the paradigms and their effects can be used to determine which factors are critical to the beneficial effects of caloric restriction ...

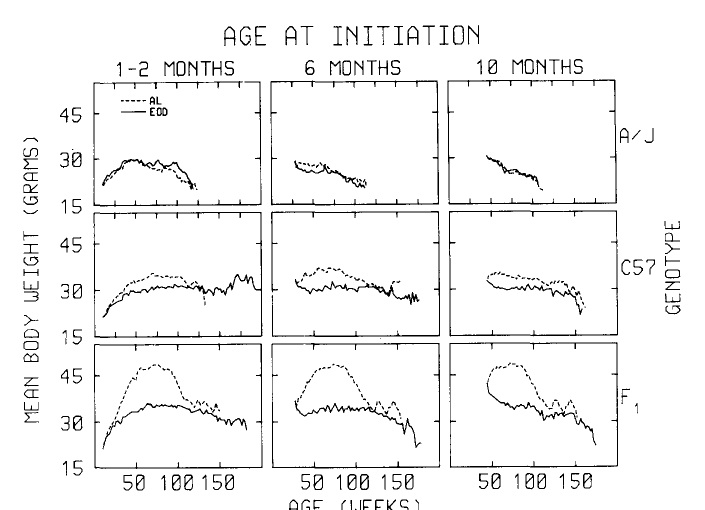

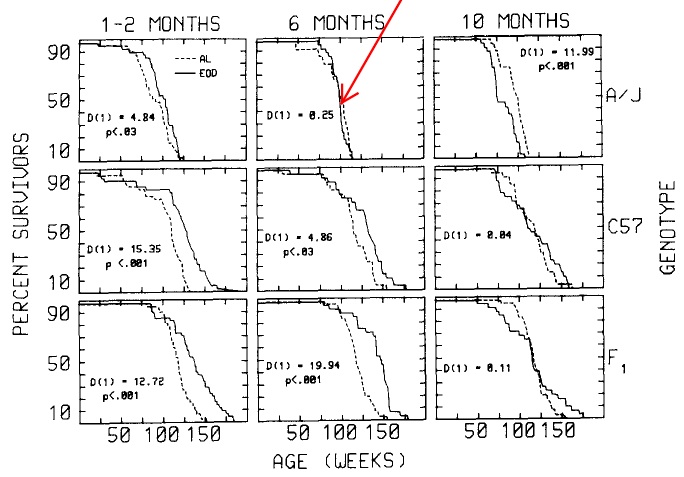

A particularly informative study of the effects of EOD feeding on mice of different genotypes was published in 1990 [1]. In that study it was reported that male A/J mice introduced as adults (6 or 10 months of age) to an EOD diet, did not decrease bodyweight and did not show any benefit in terms of longevity. In fact, those in the EOD group died early. In contrast, the maximum life span of male C57BL/6J mice begun on EOD at any age was increased. They also showed little change in bodyweight. (As noted elsewhere in this review, this is now known to be due to their ability to gorge when provided with food [5].) The F1 cross of the two strains responded well to EOD in terms of life span, but were unable to maintain bodyweight. In another study on the same mice, both EOD and LD groups were included. EOD feeding increased maximum life span by 56%, LD by 36% [2]. In contrast to these rather dramatic life span extensions, a mere 11% increase was seen in an earlier study [3]. (4)

I read that article when it was hot off the press, and later papers by the same authors (and Mark Mattson, another prominent EOD researcher). I thought at the time that the evidence strongly argued that their thesis would not pan out, for reasons that I explain here. But in looking back at this particular review, I see that even then, the analysis in (4) was deeply flawed. This post documents these errors of fact and reasoning; apologies for partially reprising arguments and analysis given in the just-linked post.

First, again, actual food intake was not measured in any of the lifespan studies cited (except for (3) -- and as we'll see, it's misused here), so the basis for the argument rests on first assuming that we can equate body weight with degree of effective CR, and then for the C57BL/6J mice combining (on the one hand) the LS results from (respectively) Goodrick, and from Ingram & Reynolds, with (on the other hand) the short-term Anson 2003 study, conducted many years later, and in another lab, in which this strain was indeed been found to gorge enough to make EOD basically isocaloric to AL.

Now, let's look at the analysis. Anson et al (4) rightly says that in (1), "A/J mice introduced as adults (6 or 10 months of age) to an EOD diet, did not decrease bodyweight [see image below] and did not show any benefit in terms of longevity. In fact, those in the EOD group died early." So in this strain, EOD let to no CR, and not only didn't lengthen LS, but shortened it.

They (4) also say, correctly, that in (1) "The F1 cross of the two strains responded well to EOD in terms of life span, but were unable to maintain bodyweight" -- ie, they lost a lot of weight (see the figure below). So for this strain, EOD apparently did lead to de facto CR -- and when you impose CR, you extend life.

But then (4) says that in the same study (1), "In contrast, the maximum life span of male C57BL/6J mice begun on EOD at any age was increased. They also showed little change in bodyweight. (As noted elsewhere in this review, this is now known to be due to their ability to gorge when provided with food; Anson et al. 2003.)"

This analysis is thus by its nature somewhat inductive, and only make sense if, as Anson et al (4) claims, (a) AL vs EOD feeding C57BL/6J mice in (1) "showed little change in bodyweight" and (b) Goodrick's mice in (1)responded to EOD as Anson's (5) did 13 years later.

But there are a lot of problems with this. First, to simply note that "the maximum life span of male C57BL/6J mice begun on EOD at any age was increased" in (1) ignores the fact that the mean LS of these mice was actually unaffected. How do you get an increase in max LS with no effect on the cohort as a whole? By having a lot of mice dying prematurely, but with the last 20% of the EOD mice still surviving at the end living sufficiently longer than the equivalent quintile of ALers to make it a wash for the average of the entire group. By contrast, with normal CR, you see an extension throughout the survival curve.

Moreover, Anson et al's (4) claim that AL vs EOD feeding to this strain in adults in (1) "showed little change in bodyweight" is questionable: they don't give the actual numbers, but the authors themselves assert that "With respect to diet effects, again the EOD regimen was effective in significantly reducing body weight among C57 and F1 genotypes at every survival quartile beyond baseline." Here are the body weight curve for animals of each strain, at each age of initiation:

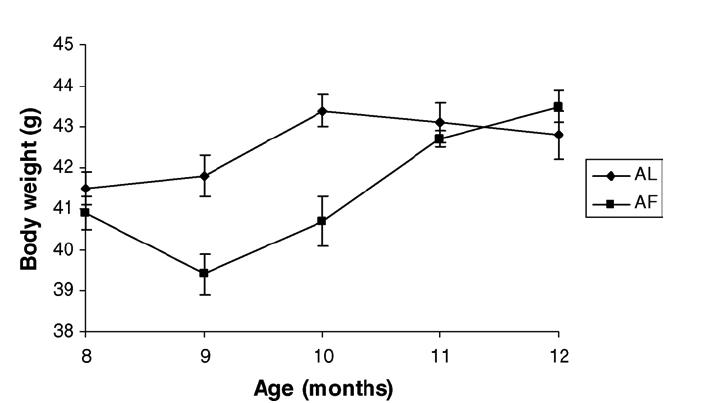

As you can see, the EOD C57 and F1 hybrid mice in this study actually did lose a significant amount of weight -- and, notably, this body weight appeared to be tied to the LS gain in the longest-lived 20%, in whom there was a full 15% body weight loss, matching up with a LS gain 6%:

(Be careful when looking at these Figures. The dashed line is the controls; the solid line is the EOD group). This is not too far off from what you'd expect from 'regular' CR, and if anything is slightly poorer. For instance, in (6), when 25% CR was initiated at a slightly older age (12 mo instead of 10), it "lowered body weight by 26% and increased maximum life span by ~15%."

So, in (1), we have 3 strains put on EOD as adults. One (A/J) didn't undergo any CR as a result, and it shortened their lives; one did undergo CR, and it lengthened their lives; and one apparently underwent relatively slight CR, and it shortened the life of most animals, but the few that struggled through an initial period of high risk enjoyed a relatively slight lifespan increase in the end. Does this sound like a vote of confidence for EOD eating? No: it shows that whatever benefits ensue come from CR, and not very safely.

Next we have Anson et al(4)'s analysis of (2), which is, simply, wrong. They claim that in C57BL/6 mice in this study "EOD feeding increased maximum life span by 56%, LD by 36%" -- but in fact, these numbers come from (2)'s Table 3, which instead shows 56% and 36% increases in mean LS. Unfortunately, (2) doesn't report maximum LS data at all; moreover, because they don't give the absolute numbers, we don't know how long-lived the controls are even on average: the strain was healthy, but certainly lots of people have managed to create bogus "life extension" effects even with healthy strains by poor housing, veterinary, or other practices, and for all we know the colony had a poor diet, an infectious epidemic, etc, against which EOD protected them in a way that is of no relevance to aging of man or mouse.

And then there's (3), of which the Anson et al review (4) says, "In contrast to these rather dramatic life span extensions, a mere 11% increase was seen in an earlier study [3]". True enough -- and that's about as much information as the abstract gives us. But for Anson to note this without further comment, in the midst of an argument that C57BL/6J mice on EOD show "little change in bodyweight" which is "now known to be due to their ability to gorge when provided with food" (again, based on the results of (5), rather than the original experiments themselves), is either totally dishonest or involved making assertions without actually reading the full text of the article, which clearly says that:

In other words, EOD, in this experiment, clearly did lead to de facto CR in C57BL/6 mice; once again, the relatively mild CR corresponds with a relatively mild life extension.On days in which the EOD animals were provided access to food, their consumption was greater than that of the AL groups; however, the data in Table I represent mean consumption averaged across all days; thus, the total dietary intake was reduced considerably by this restriction regimen. At 8 mth of age, the mean daily food intake of the EOD group was approximately 72% of that consumed by the AL group, while at 26 mth the intake of the EOD group was about 86% of that of the AL group.(3)

Again, the evidence is consistent: EOD extends lifespan to the extent that it leads to lower Calorie intake, and fails to the extent that it does not.

And, as linked above, this year we finally had a genuinely proper and direct test of the EOD hypothesis using C57BL/6 mice, involving one of the authors of (4) (Rafael de Cabo) as principal investigator. In this study, EOD-fed animals gorged on their 'feast' day, so that there was very little net reduction in food intake or body weight, just as Anson, de Cabo, and Mattson had earlier reported in (5) and used as the basis for the claim in (4) that this strain undergoes "little change in bodyweight" in response to EOD, "due to their ability to gorge when provided with food". And the result: surprise, surprise: adult-onset EOD, with very little resulting CR, lead to a small, non-statistically-significant effect on mean LS, and none at all on max.

The only real inconsistency amongst these studies is the question of why C57BL/6 mice fully compensate for their fasting days in Anson and Mattson's hands, and not in the other labs. One speculation on my part that labs in the 80s and 90s may have used food that was somewhat less energy-dense than in the later studies by Anson, Mattson, and de Cabo, making it harder to stuff down enough food to fully compensate for a day without.

Conclusion: again, EOD works to the extent that it operates as a way of imposing CR, and fails to the extent that animals compensate with extra food on their non-fasting day. If people still want to practice CR via EOD (because some find it easier to go a whole day without food than to eat regular, controlled meals) , then I think that you need to consider that this is a riskier, less consistently effective protocol, with apparently little benefit in humans and inconsistent benefits in mice; that you really ought to ease into it even more carefully than into regular CR, both because adult-onset CR generally doesn't work when imposed all at once, and because (1) clearly shows that there are risks to this EOD method in adult-onset and because it strikes me as being even more of a shock to the system than regular CR; and remember that it pretty clearly only works to the extent that it's a way f practicing an actual reduction in Calories, which you will still need to actively monitor by weighing and measuring your food, just you would by the standard protocol.

-Michael

References

1. Goodrick CL, Ingram DK, Reynolds MA, Freeman JR, Cider N.

Effects of intermittent feeding upon body weight and lifespan in inbred mice: interaction of genotype and age.

Mech Ageing Dev. 1990 Jul;55(1):69-87.

PMID: 2402168

2. Ingram DK, Reynolds MA (1987). The relationship of body weight to longevity within laboratory rodent species. In: Woodhead AD and Thompson KH (eds) Evolution of Longevity in Animals, pp 247Y282. Plenum Press, New York

3. Talan MI, Ingram DK.

Effect of intermittent feeding on thermoregulatory abilities of young and aged C57BL/6J mice.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1985 Oct;4(3):251-9.

PMID: 4074024

4. Anson RA, Jones B, de Cabo R.

The diet restriction paradigm: a brief review of the effects of every-other-day feeding

AGE. 2005 Mar; 27(1):17-25.

5. Anson RM, Guo Z, de Cabo R, Iyun T, Rios M, Hagepanos A, Ingram DK, Lane MA, Mattson MP.

Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 13;100(10):6216-20. Epub 2003 Apr 30.

PMID: 12724520 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

6. Pugh TD, Oberley TD, Weindruch R.

Dietary intervention at middle age: caloric restriction but not dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate increases lifespan and lifetime cancer incidence in mice.

Cancer Res. 1999 Apr 1;59(7):1642-8.

PMID: 10197641 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

7. Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, Peshkin L, Price NL, Labinskyy N, Swindell WR, Kamara D, Minor RK, Perez E, Jamieson HA, Zhang Y, Dunn SR, Sharma K, Pleshko N, Woollett LA, Csiszar A, Ikeno Y, Le Couteur D, Elliott PJ, Becker KG, Navas P, Ingram DK, Wolf NS, Ungvari Z, Sinclair DA, de Cabo R.

Resveratrol Delays Age-Related Deterioration and Mimics Transcriptional Aspects of Dietary Restriction without Extending Life Span.

Cell Metab. 2008 Aug;8(2):157-68.

PMID: 18599363 [PubMed - as supplied by publisher]

Edited by Michael, 18 December 2011 - 02:00 PM.