I would suspect the lock-down can be largely lifted for the simple fact that it is now Summer, and influenza and coronaviruses typically do best in the Winter.

The Reason for the Season: why flu strikes in winter

“Did you get your flu shot?” If your friends are anything like mine, you heard this question at least a dozen times before Thanksgiving. You probably got your fair share of disdainful looks too, if you answered “No.” But why are we worried about getting the flu shot now and not in May? Why is there a flu season at all? After all, what does a virus living in a host who provides a dependable, cozy incubation chamber of 98°F, care whether it is freezing and snowy outside or warm and sunny? This question has bothered people for a long time, but only recently have we begun to understand the answer.

What is the Flu?

In order to discuss why we have a flu season, we must first understand what the flu is. The flu, also called influenza, is a viral respiratory illness. A virus is a microscopic infectious agent that invades the cells of your body and makes you sick. The flu is often confused with another virus, the common cold, because of the similarity in symptoms, which can include a cough, sore throat, and stuffy nose. However, flu symptoms also include fever, cold sweats, aches throughout the body, headache, exhaustion, and even some gastro-intestinal symptoms, such as vomiting and diarrhea (1).

The flu is highly contagious. Adults are able to spread the virus one day prior to the appearance of symptoms and up to seven days after symptoms begin. Influenza is typically spread via the coughs and sneezes of an infected person (1). Around 200,000 people in the United States are hospitalized each year because of the flu, and of these people, about 36,000 die. The flu is most serious for the elderly, the very young, or people who have a weakened immune system (1).

The Flu Season

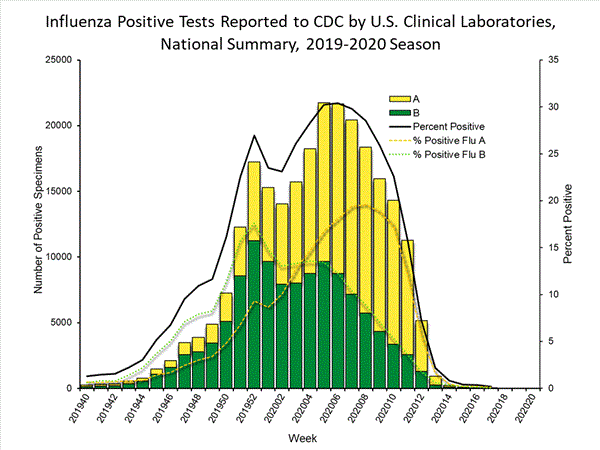

The flu season in the U.S. can begin as early as October, but usually does not get into full swing until December. The season generally reaches its peak in February and ends in March (2). In the southern hemisphere, however, where winter comes during our summer months, the flu season falls between June and September. In other words, wherever there is winter, there is flu (3). In fact, even its name, “influenza” may be a reference to its original Italian name, influenza di freddo, meaning “influence of the cold” (4).

A common misconception is that the flu is caused by cold temperatures. However, the influenza virus is necessary to have the flu, so cold temperatures can only be a contributing factor. In fact, some people have argued that it is not cold temperatures that make the flu more common in the winter. Rather, they attest that the lack of sunlight or the different lifestyles people lead in winter months are the primary contributing factors. Here are the most popular theories about why the flu strikes in winter:

1) During the winter, people spend more time indoors with the windows sealed, so they are more likely to breathe the same air as someone who has the flu and thus contract the virus (3).

2) Days are shorter during the winter, and lack of sunlight leads to low levels of vitamin D and melatonin, both of which require sunlight for their generation. This compromises our immune systems, which in turn decreases ability to fight the virus (3).

3) The influenza virus may survive better in colder, drier climates, and therefore be able to infect more people (3).

The Flu Likes Cold, Dry Weather

For many years, it was impossible to test these hypotheses, since most lab animals do not catch the flu like humans do, and using humans as test subjects for this sort of thing is generally frowned upon. Around 2007, however, a researcher named Dr. Peter Palese found a peculiar comment in an old paper published after the 1918 flu pandemic: the author of the 1919 paper stated that upon the arrival of the flu virus to Camp Cody in New Mexico, the guinea pigs in the lab began to get sick and die (4). Palese tried infecting a few guinea pigs with influenza, and sure enough, the guinea pigs got sick. Importantly, not only did the guinea pigs exhibit flu symptoms when they were inoculated by Palese, but the virus was transmitted from one guinea pig to another (4).

Now that Palese had a model organism, he was able to begin experiments to get to the bottom of the flu season. He decided to first test whether or not the flu is transmitted better in a cold, dry climate than a warm, humid one. To test this, Palese infected batches of guinea pigs and placed them in cages adjacent to uninfected guinea pigs to allow the virus to spread from one cage to the other. The pairs of guinea pig cages were kept at varying temperatures (41°F, 68°F, and 86°F) and humidity (20%-80%). Palese found that the virus was transmitted better at low temperatures and low humidity than at high temperatures and high humidity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 ~ Experimental Setup. Guinea pigs were housed in adjacent cages. Guinea pigs in cage 1 were infected by Palese with influenza. Palese observed how many guinea pigs in cage 2 became infected from the guinea pigs in cage 1 at different temperatures and levels of humidity. B, C) Transmission rates were 100% at low humidity, regardless of temperature. At high humidity, transmission occurred only at the lower temperature.

However, Palese’s initial experiment did not explain why the virus was transmitted best at cooler temperatures and low humidity. Palese tested the immune systems of the animals to find out if the immune system functions poorly at low temperatures and low humidity, but he found no difference in innate immunity among the guinea pigs (5). A paper from the 1960s may provide an alternate explanation. The study tested the survival time of different viruses (i.e. the amount of time the virus remains viable and capable of causing disease) at contrasting temperatures and levels of humidity. The results from the study suggest that influenza actually survives longer at low humidity and low temperatures. At 43°F with very low humidity, most of the virus was able to survive more than 23 hours, whereas at high humidity and a temperature of 90°F, survival was diminished at even one hour into incubation (3).

The data from these studies are supported by a third study that reports higher numbers of flu infections the month after a very dry period (6). In case you’re wondering, this is only the case in places that experience winter. In warmer climates, oddly enough, flu infection rates are correlated most closely with high humidity and lots of rain (6). Unfortunately, not much research has been done to explain these contradictory results, so it’s unclear why the flu behaves so differently in disparate environments. This emphasizes the need for continued influenza research. Therefore, we can conclude that, at least in regions that have a winter season, the influenza virus survives longer in cold, dry air, so it has a greater chance of infecting another person.

Although other factors probably contribute as well, the main reason we have a flu season may simply be that the influenza virus is happier in cold, dry weather and thus better able to invade our bodies. So, as the temperature and humidity keep dropping, your best bet for warding off this nasty bug is to get your flu shot ASAP, stay warm, and invest in a humidifier.