In an open-access paper published in Cell Stem Cell this month, researchers have explained how organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are being used to analyze diseases and develop treatments.

Different sources for different conditions

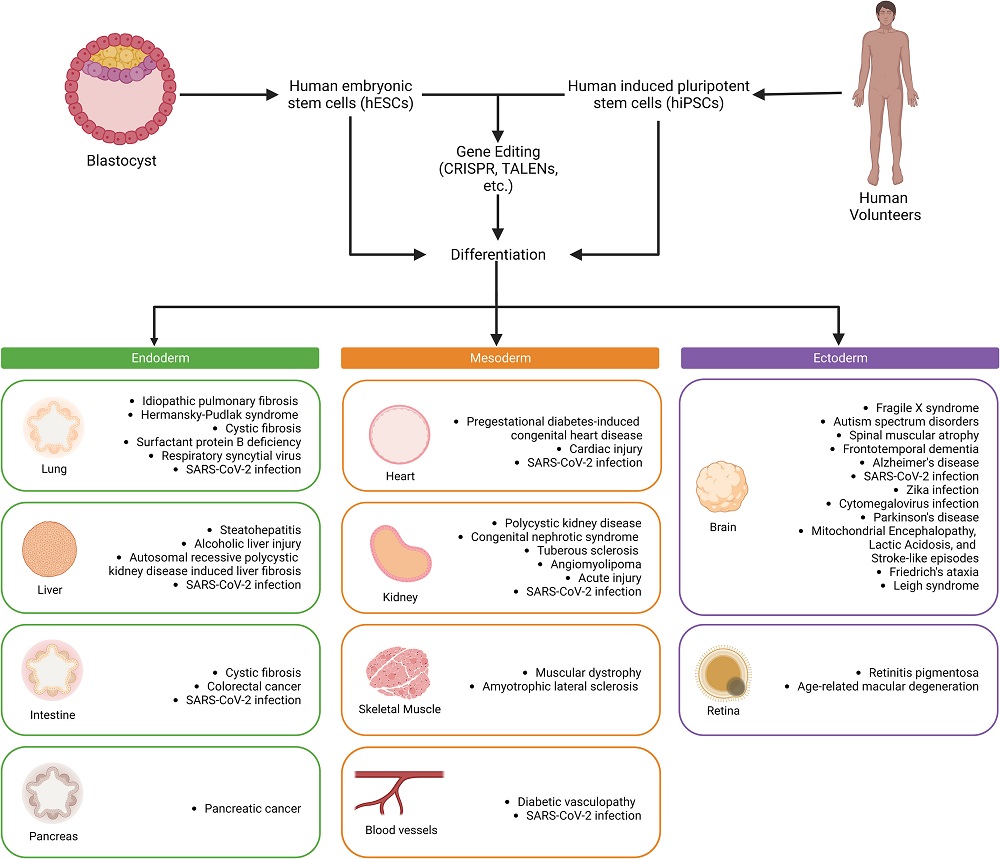

This review includes both human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), which are derived from the human organism at its very earliest life stages and have been around for a quarter century [1], and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which have existed for 17 years and are created by taking existing cells and reverting them to a pluripotent state [2].

These two types are generally used in different research focuses. hESCs are often used to study the cellular effects of genetic modification, such as in genetic diseases. iPSCs, on the other hand, are valuable for studying the effects of existing diseases, including age-related diseases, because they can be taken from afflicted patients and a healthy control group.

An upgrade from 2D to 3D allows tissue generation

Cellular analysis has come a long way from the petri dish. For an organoid to be an actual miniature organoid instead of just a collection of cells, it needs to have blood vessels (vascularization) along with distinct populations of stem cells and functional cells, just like in natural organs. This cannot be done on a flat sheet.

A great many organoid types have already been created and are in regular use. Lung organoids, in particular, became popular for analyzing the effects of the infamous SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Cystic fibrosis and genetic disorders are also popular lung targets, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which appears to be age-related, has also been studied.

The heart is another key target, and we have already discussed how some particular heart organoids might be useful in researching age-related diseases. Organoids allow for the analysis of many other diseases as well, including congenital heart defects, and they let researchers safely test drugs thar promote cellular proliferation in the heart. These drugs may also one day be useful against heart aging.

This technology also offers potential liver benefits. Although it is known for its regenerative capacity, liver tissue is vulnerable to diseases such as hepatitis, and alcohol’s effects on the liver are well known. The reviewers note that there are no drugs to treat alcoholic liver disease, and organoids might be the right vehicle with which to find them.

Kidney tissue is also a concern, and intestinal, and pancreatic tissue are undergoing similar tests as well. While vascularization is a prerequisite for functional organoids, the blood vessels themselves are often a topic of consideration.

Most notably, particularly in the context of aging, brain organoids can also be created. The differences between the common allele ApoE3 and its Alzheimer’s-linked counterpart ApoE4 have been tested in organoids [3], and some analysis on the effects of removing amyloid beta has already been done [4]. Parkinson’s disease is another target, as are genetic problems such as fragile X syndrome and Friedreich’s ataxia along with mitochondrial disorders.

Not yet the end of mouse studies

Mice, particularly genetically altered mice, are the predominant standard in preclinical drug development, and for good reason: they grow quickly and are relatively easy to keep, and modifying them is becoming an increasingly standardized and simple affair. However, even with the various genetic modifications, mice are still not human beings, and the differences may explain some clinical trial failures: not every drug that works in mice works as well in people.

Of course, organoids do not match full human beings either. While the state of the art outlined in this paper involves fully modeled subsystems, each of these subsystems still doesn’t include all the cells, endocrine factors, and tissues in a human being, particularly when aging is brought into the picture. Therefore, it is unlikely that organoids can broadly replace mice in every circumstance; instead, it’s much more likely that these techniques could be used in tandem, combining the human elements of the organoid with the whole-body analysis of the mouse.

Aside from stem cells used in therapies, it is our hope that advancements in technology will allow for the efficient creation of more organoids that are subject to age-related diseases, making them effective testing grounds for interventions against aging.