A new review authored by three acclaimed geroscientists paints a promising picture of past and ongoing human clinical trials of prospective anti-aging drugs [1].

From worms and mice to humans

The biology of aging is an exciting new field, but most of its successes have been in animal models, from the early breakthroughs in yeast [2] and nematode worms [3] to the robust findings by the ITP (Intervention Testing Program) in mice [4]. Human data, however, is much scarcer. Some potentially geroprotective interventions, such as cellular reprogramming, are brand new, so they are yet to be tested in clinical trials. Others are well-known drugs that have been in use for various indications, and we have reasons to believe that they might also prolong human lifespan.

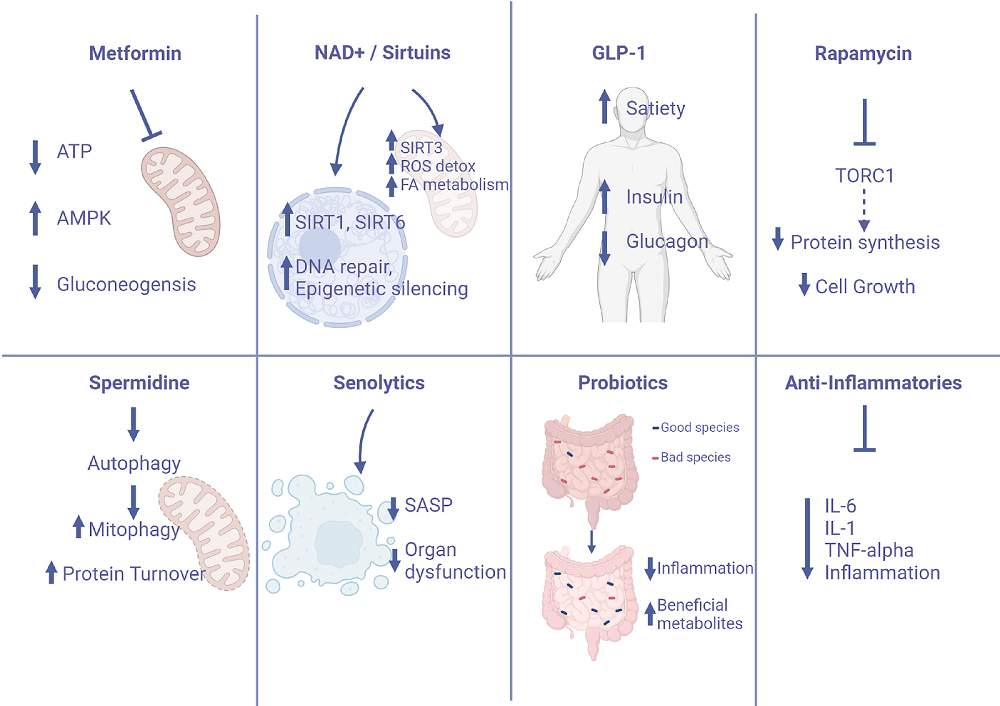

In this new review published in Cell Metabolism, three renowned aging researchers – David Sinclair of Harvard, Leonard Guarente of MIT, and Guido Kroemer of Université Paris Descartes – summarized the current state of affairs in human trials of potentially geroprotective drugs. They focused on eight categories: metformin, NAD+/sirtuins, GLP-1, rapamycin, spermidine, senolytics, probiotics, and anti-inflammatories. After providing a brief overview of the related compounds and their mechanisms of action, the authors delved into past and ongoing trials.

Metformin

Metformin was isolated decades ago from French lilac, which is a traditional anti-diabetes medication. However, it has only been used widely since the 1990s, to great success. Interestingly, it remains unclear how exactly metformin helps diabetes patients, but the leading theory is that it weakly inhibits mitochondrial respiratory complex I, which via the activation of AMPK kinase lowers glucose production and stimulates mitochondrial activity. However, other explanations have been proposed.

Metformin became geroscience’s darling after a 2014 study showed that diabetes patients on metformin tended to live longer than age-matched healthy people. A recent 2023 study questions this assumption, but the authors interpret its results as less than a death blow to metformin’s prospects as a geroprotective drug.

So far, in human trials, metformin has been shown to protect heart function in diabetics, improve immune function (in a small-scale trial), and lower one marker of inflammation (CRP), but not another marker (IL-6). The authors also note that metformin slightly dampens the effects of aerobic exercise, probably due to attenuation of mitochondrial function. However, it is not clear at this point whether it should be seen as a serious problem for people who exercise a lot.

NAD+ and sirtuins

NAD+ is a ubiquitous and multi-purpose molecule that mediates energy production and serves as a substrate for the family of enzymes called sirtuins. Sirtuins play various roles, including in DNA repair and mitochondrial maintenance, and their activation has been shown to extend lifespan in numerous animal models. In addition to NAD+ supplementation, some sirtuins can be activated directly by compounds such as resveratrol, quercetin, and fisetin.

Human trials on the NAD+ precursors NMN and NR have shown that those can reliably elevate NAD+ levels. One NMN trial led to higher physical performance and lower biological age in middle-aged adults. Two trials of SIRT1 activator pterostilbene demonstrated improved liver function. MIB-626, an NMN polymorph developed by Sinclair’s company Metro Biotech, was found to improve lipid profile and diastolic blood pressure. NR trials in patients with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or ALS have shown some promise, and many more trials are currently running.

GLP-1

GLP-1 is a hormone produced in response to food intake and it is known to stimulate insulin secretion and mediate satiety. GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, are novel anti-diabetes drugs that have become widely popular due to their impressive effectiveness in promoting weight loss.

Since diabetes and obesity are strongly associated with one another and with various diseases of aging, GLP-1R agonists have the potential to be highly effective anti-aging agents. Accordingly, two large trials showed that semaglutide and liraglutide improve cardiovascular function and decrease cardiovascular mortality. Two other studies demonstrated some positive effects of GLP-1R agonists in Parkinson’s patients.

Rapamycin and mTOR

Rapamycin is yet another FDA-approved medication that has been around for many years. It is mostly used as an immunosuppressant, but it has also been found to extend lifespan and healthspan in various animal models, including mice, even when given late in life. Rapamycin works by inhibiting mTOR, a protein complex that mediates protein production and cell growth.

Studies of everolimus, a rapamycin analog, showed increased immune response to influenza vaccination and lower infection rate over a one-year period, which is somewhat surprising given that rapamycin is an immunosuppressant. The authors suggest that everolimus, which selectively targets only one of the mTOR components, TORC1, might be less toxic. Rapamycin was also shown to reduce a subset of pro-inflammatory T cells in lupus and to cause some skin rejuvenation.

The authors, however, emphasize rapamycin’s side effects. By slowing protein synthesis, it probably blunts the effects of exercise and slows wound healing, among other things. Just like metformin, rapamycin might be ill-advised for people with high levels of physical activity, although this remains to be seen.

Spermidine

Spermidine is a natural metabolite of the polyamine family that has been found to increase lifespan in animal models, including in mice, albeit modestly, compared to rapamycin. Spermidine is known to induce autophagy, the process of clearing out accumulated cellular junk such as misfolded proteins.

Since autophagy targets protein aggregates, including amyloid beta, spermidine has been tested for possible cognitive function effects and shown to improve cortical thickness and hippocampal volume in older adults. Two other studies demonstrated cognitive improvements.

Spermidine is found in food, so populational studies are possible. Two retrospective studies, from Italy and Austria, reported inverse correlation between spermidine intake and mortality.

Senolytics

Senolytics are a completely new class of drugs that didn’t exist just several years ago. They supposedly clear out senescent cells – those that became dysfunctional and stopped proliferating, but remain in the body, causing inflammation and other types of harm.

Despite the amount of interest in senolytics both in academia and in the private sector, completed human trials are still very sparse. The authors mention mostly those that show the ability of senolytics to clear out senescent cells. However, many trials are underway, so stay tuned. Interestingly, the review does not mention the failure in 2020 of UNITY’s lead senolytic candidate, UBX0101.

Probiotics

The importance of microbiome for aging is a relatively new finding. Studies have demonstrated that aging changes gut microbiota composition and that transplanting young microbiota confers various health benefits and can increase lifespan in progeroid mice.

Probiotics have been demonstrated to improve immune function, increasing the number of T cells and lowering the number and duration of common infectious diseases. Several studies have reported that a healthier microbiome can improve cancer outcomes.

Microbiota naturally have a big impact on metabolism. Beneficial bacteria (mostly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) can improve lipid profiles and increase insulin sensitivity. Probiotics can also lower inflammation and improve cognitive function.

Anti-inflammatories

Finally, since chronic inflammation is one of the hallmarks of aging, the whole formidable arsenal of anti-inflammatory drugs, including steroids, analgesics, and monoclonal antibodies against particular inflammatory molecules, have considerable anti-aging potential. Most of the completed trials, according to the authors, deal with the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. Reducing its levels has been shown to improve the symptoms of irritable bowel disease and ulcerative colitis.

The authors, however, warn about tinkering with inflammatory cytokines, since those mediate immune responses. One study reported that treatment with tocilizumab, an IL-6-neutralizing antibody, leads to an increase in infections. Among other anti-inflammatories, the good old aspirin is featured in several ongoing trials, including for prevention of cancer in at-risk patients. One completed trial found that aspirin was associated with lower mortality in people at least 70 years old. As with other drug categories mentioned in the review, there are numerous ongoing trials of anti-inflammatory agents.

Aging research over the past three decades has unveiled numerous pathways that may be targeted for interventions to slow aging processes and their accompanying diseases. This review has sketched out some of the leading candidates under current scrutiny, although it is possible that other approaches will reveal themselves in the future. We believe that the next few years will present a tipping point, when the most viable approaches will become evident and move us toward a more widespread use of interventions targeting aging processes. While aging is not a disease as prescribed by the FDA, one might expect approval of these interventions to treat aging-fostered diseases.

Literature

[1] Guarente, L., Sinclair, D. A., & Kroemer, G. (2024). Human trials exploring anti-aging medicines. Cell Metabolism.

[2] Kaeberlein, M., McVey, M., & Guarente, L. (1999). The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes & development, 13(19), 2570-2580.

[3] Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A., & Tabtiang, R. (1993). A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature, 366(6454), 461-464.

[4] Harrison, D. E., Strong, R., Sharp, Z. D., Nelson, J. F., Astle, C. M., Flurkey, K., … & Miller, R. A. (2009). Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. nature, 460(7253), 392-395.

View the article at lifespan.io