An analysis of data from over twenty thousand people has indicated that greater dietary diversity is associated with slower biological aging [1].

Your health is what you eat

Good dietary habits are linked to many health benefits, and different diets were previously reported to impact the speed of aging and senescence. For example, adherence to the Mediterranean diet is positively associated with increased lifespan and healthspan.

We have also previously reported on some health benefits linked to different dietary patterns, such as associations linking an anti-inflammatory diet and the Mediterranean diet with a reduced risk of dementia, the positive impact of a ketogenic diet on symptoms of multiple sclerosis, the impact of Mediterranean, keto, and plant-based diets on cancer risk and progression, and the metabolic benefits of a ketogenic diet and the Mediterranean diet in pre-diabetes and Type 2 diabetes patients.

The authors of this study did not focus on any specific diet; instead, they focused on the diversity of food consumed by the study participants. They discuss the impact of a diverse diet, which is rich in macronutrients, micronutrients, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds, on the speed of aging.

Biological age is not just a number

Compared to chronological age alone, the relationship between biological age and chronological age is a better estimate of health and the risk of developing age-related diseases. A higher biological age suggests a higher possibility of developing age-related diseases and a higher chance of dying.

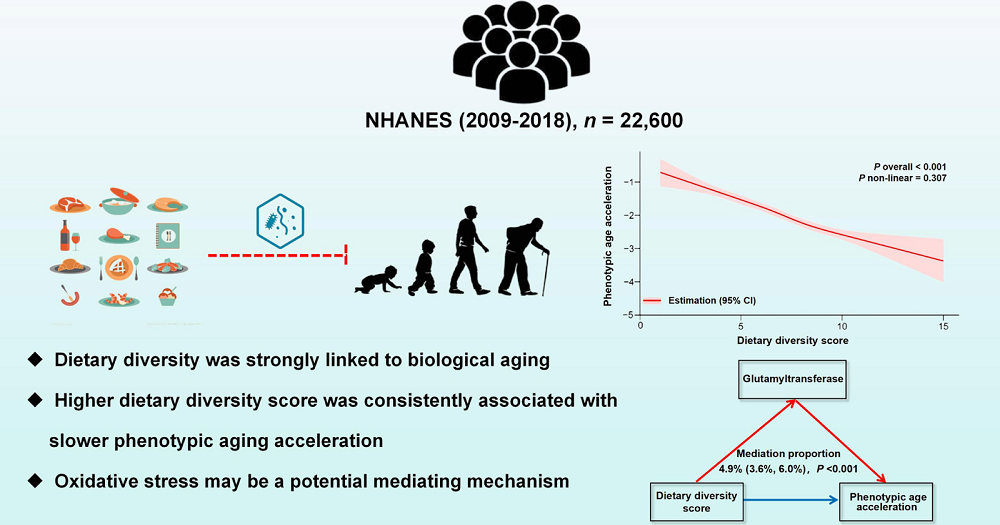

The researchers analyzed data from 22,600 participants (49.3% male) with an average age of 48 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-sectional survey conducted in the United States. People under 20 years of age, pregnant, and those with no available food intake or biological age data were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers in this study used phenotypic age and Klemera–Doubal method (KDM) biological age to represent the biological age of study participants. Those measures are based on the composite clinical biomarkers.

They used systolic blood pressure, blood creatinine, urea nitrogen, albumin, total cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, percentage of lymphocytes, mean erythrocyte volume, leukocyte count, and alkaline phosphatase as biomarkers for their assessment.

The more diverse, the better

The researchers assessed the dietary diversity score (DDS), which was described as simple, effective, and validated in clinical trials. It measures the number of food groups in one’s diet, based on five major food groups and 18 subgroups. “A higher DDS is generally indicative of a more varied diet and is associated with a broader intake of essential nutrients.” Previous research had reported an association between a higher DDS and a lower risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus [2] and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [3].

In the analyzed group, the researchers measured DDS based on the average score from two self-reported 24-hour dietary recalls.

Higher diversity, lower biological age

The researchers used a few models to analyze the data. In the first model, they didn’t include any confounding variables. The second and third models were adjusted for different factors. Model two included demographic factors. The third model also included health metrics, such as cancer, smoking, alcohol consumption, and metabolic data. The researchers performed multiple modeling analyses using different variables (continuous and categorical) and corrected for multiple confounders.

Their results suggested an association between higher DDS and slower biological aging. They note that this relationship is both highly significant (overall p of under 0.001) and linear.

Analysis of the participants’ subgroups divided by different health or demographic factors suggested an inverse relationship between DDS and phenotypic age acceleration across subgroups; however, these results were mainly not statistically significant.

The researchers also performed a sensitivity analysis that ensured the robustness of their observations. They did this analysis using multiple adjustments and concluded that the consistency of all three models suggests “a higher dietary diversity is significantly associated with lower phenotypic age acceleration, regardless of the adjustment methods employed.”

The researchers also explored the idea of oxidative stress being the factor mediating the relationship between dietary diversity and aging. They observed that “the oxidative stress indicator GGT had a significant mediating effect on the association of DDS and phenotypic age acceleration.”

Glutamyltransferase (GGT) was one of the proteins that was significantly lower in people with higher DDS. White blood cell count and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, two indicators of inflammation, were also significantly reduced. In contrast, levels of albumin, a potential indicator of anti-inflammatory capacity, and serum klotho, a protein with anti-aging properties, were higher.

Robust results, but without mechanistic understanding

Since this study is based on observational data, it cannot determine the mechanism behind the observed association. Still, the researchers proposed some hypotheses. They believe that oxidative stress and inflammation could be key processes mediating the effect of diet on aging, as a more diverse diet includes more antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds that protect cells from aging-related processes. They also consider the possible role of gut microbiota since a diverse diet can help maintain microbial diversity, an important factor for gut health. However, that particular aspect was not explored in this study.

The researchers claim that their results are robust and can be extrapolated to multi-ethnic and otherwise varied populations due to this data’s consistency and analysis.

While this analysis suggested that some associations are mediators, it cannot establish causality, and potential confounding factors (beyond what was tested) cannot be ruled out. The reporting of food intake should also be optimized for future studies.

Overall, this study’s results align with previous research, which linked reduced food diversity to an increased risk of age-related chronic diseases and mortality [2-5]. As the authors note, “promoting dietary diversity may facilitate healthy aging, which has significant implications for public health.”

Literature

[1] Liao, W., & Li, M. Y. (2024). Dietary diversity contributes to delay biological aging. Frontiers in medicine, 11, 1463569.

[2] Zheng, G., Cai, M., Liu, H., Li, R., Qian, Z., Howard, S. W., Keith, A. E., Zhang, S., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Lin, H., & Hua, J. (2023). Dietary Diversity and Inflammatory Diet Associated with All-Cause Mortality and Incidence and Mortality of Type 2 Diabetes: Two Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients, 15(9), 2120.

[3] Chalermsri, C., Ziaei, S., Ekström, E. C., Muangpaisan, W., Aekplakorn, W., Satheannopakao, W., & Rahman, S. M. (2022). Dietary diversity associated with risk of cardiovascular diseases among community-dwelling older people: A national health examination survey from Thailand. Frontiers in nutrition, 9, 1002066.

[4] Zheng, G., Xia, H., Lai, Z., Shi, H., Zhang, J., Wang, C., Tian, F., & Lin, H. (2024). Dietary Inflammatory Index and Dietary Diversity Score Associated with Sarcopenia and Its Components: Findings from a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 16(7), 1038.

[5] Chalermsri, C., Rahman, S. M., Ekström, E. C., Ziaei, S., Aekplakorn, W., Satheannopakao, W., & Muangpaisan, W. (2023). Dietary diversity predicts the mortality among older people: Data from the fifth Thai national health examination survey. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 110, 104986.

View the article at lifespan.io