Reseachers publishing in Antioxidants have combined three antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds and tested their effects in human beings.

A Clinical Trial of a Three-Part Treatment for Inflammaging

#1

Posted 02 December 2024 - 09:59 PM

The first component the researchers included was AM3, a compound that is core to the Inmunoferon supplement and is an immunomodulator that has been found in trials to aid against infections [1]. Some prior work has found that AM3 also assists against immunosenescence [2]. However, as these researchers note, little work has been done in that area, and that work did not establish whether or not it could do anything to curtail age-related immune dysfunction.

The second component was spermidine, a polyamine that has been reported to improve the cellular maintenance process known as autophagy, thereby also ameliorating immunosenescence [3]. Spermidine has also been reported to assist in gut function by returning macrophage polarization to a less inflammatory state [4].

The third component was hesperidin, a flavonoid that recent prior work had found to have potential effects against multiple diseases, including hepatitis [5] and several metabolism-related disorders, such as diabetes [6], obesity [7], and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [8]. The researchers hold that these effects most likely originate from its effects against inflammation, such as its suppression of the senescence-related protein MMP-9 [9], and on immune response [10].

All three of these ingredients are sold in various parts of the world as supplements and are generally considered nontoxic. No side effects were noted in this study.

Effects on inflammation, oxidation, and immune function

A total of 35 healthy people aged between 30 and 60 years old completed this study, which lasted for two months. The doses of these three compounds are distinctly different: 150 milligrams of an AM3-containing compound and 50 milligrams of hesperidin were included alongside only .6 of a milligram of spermidine.

As their primary target, the researchers utilized ImmunolAge, an immune system-based metric that calculates such factors as neutrophil activity and natural killer activity [11], as their measurement of biological age. They noted that the participants in both the placebo and treatment groups had, on average, an ImmunolAge of 20 years over chronological age, which the researchers ascribed to the stress and anxiety that the participants were reporting at baseline.

The placebo effect was not statistically significant, while ImmunolAge was significantly decreased in the supplement group by approximately 10 years. While this finding is strongly positive, the researchers also note that this was still higher by a decade than the participants’ chronological ages.

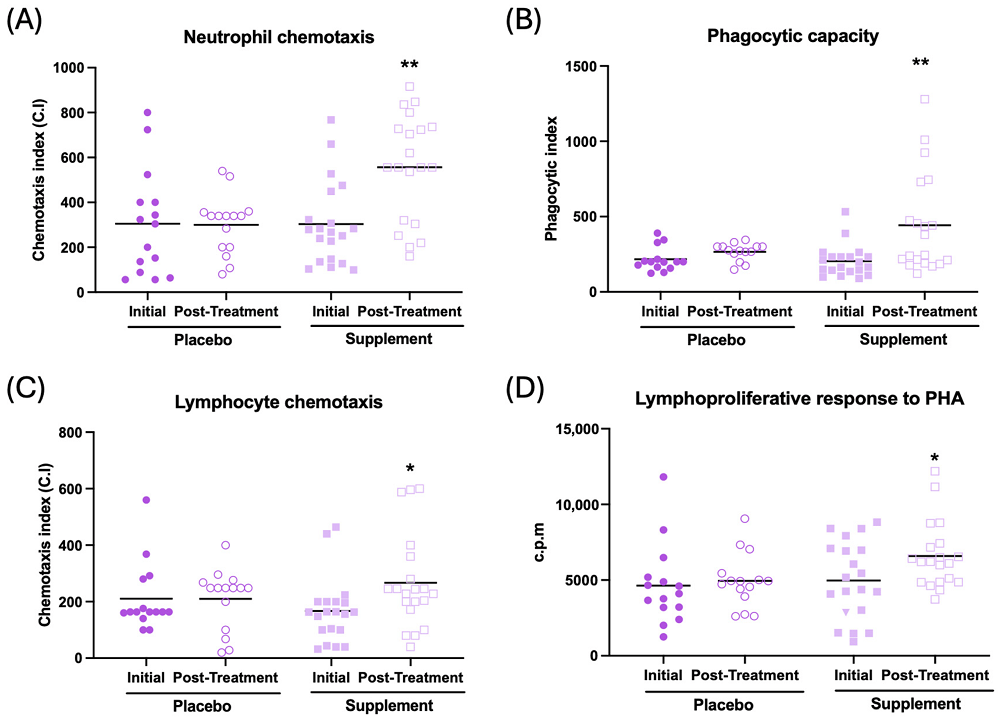

This difference in ImmunolAge was due to stronger responsiveness of both neutrophils and lymphocytes along with an increase in phagocytosis, the ability of immune cells to engulf and consume pathogens. In general, the cells were more responsive to perceived threats and more willing to attack them. Despite these benefits to other immune cell types, natural killer cells were unaffected.

This increase in immune responsiveness was accompanied by significant decreases in circulating inflammation. The well-known inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β were significantly decreased, while the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 was increased. However, the inflammatory factor IL-6 was also increased.

Oxidative stress was also significantly affected by this supplement combination. The natural antioxidant glutathione was found to be more active, while the amount of used, oxidized glutathione in the blood was decreased.

Moreover, the researchers hold that this supplement combination has significant effects on oxi-inflammaging, a combination of oxidative stress and inflammaging that has been suggested to have significant effects on lifespan [12].

More research needed

While this was a randomized, controlled trial with significant positive results, it was a pilot trial of only 35 people, not a Phase 2 or larger Phase 3 trial. This trial solely used an immune system-based calculation as a proxy for biological age; no epigenetic clock was used, and other lifespan-related biomarkers were not obtained. Cellular senescence, which the researchers had mentioned and was likely to be affected by the circulating biomarkers studied here, was also not directly analyzed. This study was conducted on a middle-aged group; it is unclear whether or not older people would have responded in the same way.

The researchers also noted that such factors as diet were not altered, with participants encouraged to continue their usual eating habits, and it was unclear how many natural antioxidants the participants were already consuming. Additionally, it is infeasible to determine if such a supplement combination can actually extend lifespan in healthy people through direct analysis, and the researchers recommend animal studies in further work.

Literature

[1] JA, G. M., & Schamann, F. (1992). Immunologic clinical evaluation of a biological response modifier, AM3, in the treatment of childhood infectious respiratory pathology. Allergologia et Immunopathologia, 20(1), 35-39.

[2] Villarrubia, V. G., Koch, M., & MC, C. C., González, S. and Alvarez-Mon, M.(1997) The immunosenescent phenotype in mice and humans can be defined by alterations in the natural immunity reversal by immunomodulation with oral AM3. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 19, 53-74.

[3] Zhang, H., & Simon, A. K. (2020). Polyamines reverse immune senescence via the translational control of autophagy. Autophagy, 16(1), 181-182.

[4] Niechcial, A., Schwarzfischer, M., Wawrzyniak, M., Atrott, K., Laimbacher, A., Morsy, Y., … & Spalinger, M. R. (2023). Spermidine ameliorates colitis via induction of anti-inflammatory macrophages and prevention of intestinal dysbiosis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 17(9), 1489-1503.

[5] Li, S., Hao, L., Hu, X., & Li, L. (2023). A systematic study on the treatment of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma with drugs based on bioinformatics and key target reverse network pharmacology and experimental verification. Infectious Agents and Cancer, 18(1), 41.

[6] Mirzaei, A., Mirzaei, A., Khalilabad, S. N., Askari, V. R., & Rahimi, V. B. (2023). Promising influences of hesperidin and hesperetin against diabetes and its complications: a systematic review of molecular, cellular, and metabolic effects. EXCLI journal, 22, 1235.

[7] Xiong, H., Wang, J., Ran, Q., Lou, G., Peng, C., Gan, Q., … & Huang, Q. (2019). Hesperidin: A therapeutic agent for obesity. Drug design, development and therapy, 3855-3866.

[8] Morshedzadeh, N., Ramezani Ahmadi, A., Behrouz, V., & Mir, E. (2023). A narrative review on the role of hesperidin on metabolic parameters, liver enzymes, and inflammatory markers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Science & Nutrition, 11(12), 7523-7533.

[9] Lee, H. J., Im, A. R., Kim, S. M., Kang, H. S., Lee, J. D., & Chae, S. (2018). The flavonoid hesperidin exerts anti-photoaging effect by downregulating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression via mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling pathways. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 18, 1-9.

[10] Camps-Bossacoma, M., Franch, À., Pérez-Cano, F. J., & Castell, M. (2017). Influence of hesperidin on the systemic and intestinal rat immune response. Nutrients, 9(6), 580.

[11] Martínez de Toda, I., Vida, C., Díaz-Del Cerro, E., & De la Fuente, M. (2021). The immunity clock. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 76(11), 1939-1945.

[12] Miquel, J. (2009). An update of the oxidation-inflammation theory of aging: the involvement of the immune system in oxi-inflamm-aging. Current pharmaceutical design, 15(26), 3003-3026.

View the article at lifespan.io