Scientists have presented GroceryDB, an open-access online database that measures the degree of processing of tens of thousands of products sold in three major US grocery chains [1].

What is ultra-processed food?

While there is no universally accepted definition, the NOVA food classification system is widely used, and it defines ultra-processed food as “industrially manufactured food products made up of several ingredients including sugar, oils, fats and salt (generally in combination and in higher amounts than in processed foods) and food substances of no or rare culinary use (such as high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils, modified starches and protein isolates).”

In other words, ultra-processed food involves breaking down “real food” and creating something mostly new, such as instant soup or candy, with a nutrient makeup unlike anything encountered in nature. This food equivalent of Frankenstein’s monster fools the gratification circuits developed by millions of years of evolution, tricking people into ingesting too much unhealthy and too little healthy food while generally overeating.

Even though ultra-processed food encompasses a wide range of different products, from beverages to sausages, as a category, it has been consistently linked to adverse health outcomes, such as cancer [2], cardiovascular disease [3], and obesity [4]. Alarmingly, people in developed nations consume up to 60% of their calories from ultra-processed food.

Getting to know your food

It is not always straightforward to know the processing of foods in a local grocery store. It is sometimes possible to make an educated guess, such as with sugary beverages, but other products are not as obvious. Unfortunately, minimalistic food labels don’t offer much help.

The group led by Prof. Albert-László Barabási, whichi included researchers from the Harvard Medical School and Northeastern University, has been studying ultra-processed food for several years. In their new paper published in Nature Food, the researchers describe GroceryDB, an open online database that contains information on more than 50,000 products offered by three major US chains: Walmart, Whole Foods Market, and Target.

Last year, the group published FPro, a food processing score that they had developed using machine learning techniques, that translates the nutritional content of a food item into its degree of processing. FPro, which powers GroceryDB, is mostly based on NOVA (it was trained to predict a NOVA category of the product from its ingredients) but can accommodate other food processing classification systems. The reliance on the list of nutrients is due to several reasons, such as that in unprocessed food, their quantities are constrained by biochemistry-determined physiological ranges.

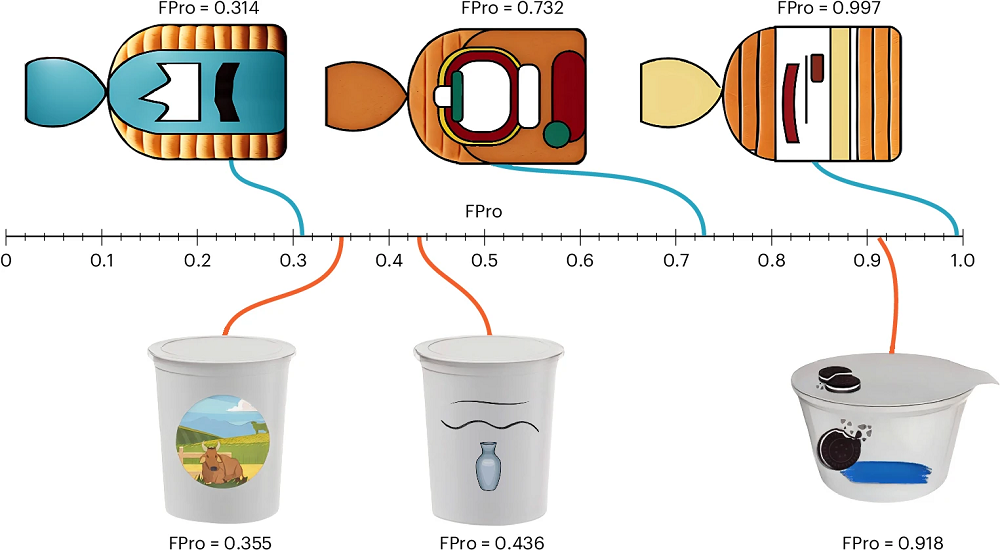

Browsing GroceryDB, available at Truefood.tech, and comparing favorite foods to less or more processed alternatives is a captivating pastime. One of the main takeaways is that the degree of food processing can vary a lot even within a single category. The paper provides several examples, starting with bread.

The tale of the two cheesecakes

A multi-grain bread from Manna Organics, sold by Whole Foods, which mostly contains whole wheat, barley, and brown rice without any additives, salt, oil, and yeast, has an FPro of 0.314 (the index ranges from 0 to 1). The two less health-oriented chains, Walmart and Target, both carry Aunt Millie’s and Pepperidge Farmhouse breads (FPros of 0.732 and 0.997, respectively) with ingredients including soluble corn fiber, sugar, resistant corn starch, wheat gluten, and monocalcium phosphate.

The researchers saw a similar picture with yogurts: Seven Stars Farm yogurt made from grade A pasteurized organic milk has an FPro of 0.355. Siggi’s yogurt, with an FPro of 0.436, uses pasteurized skim milk, which, according to the paper, requires more food processing to eliminate fat. The two pale in comparison to Chobani Cookies and Cream yogurt with its whopping FPro of 0.918, thanks to loads of cane sugar and multiple additives such as caramel color, fruit pectin, and vanilla bean powder.

Some food categories are inherently highly processed, so it is unlikely to find cookies with a low FPro. However, even in those categories, the distribution of FPro scores is quite wide, and healthier alternatives are available. Unsurprisingly, the prevalence of less processed food was much higher in Whole Foods Market than in the other two chains.

The researchers highlighted one of the reasons for the abundance of ultra-processed food: processing decreases the cost per calorie. Across all GroceryDB categories, a 10% increase in FPro leads to an 8.7% decrease in the price per calorie. In some categories, the decline is much steeper, however, with milk, the relationship is reversed, probably due to more expensive plant milks also being more processed.

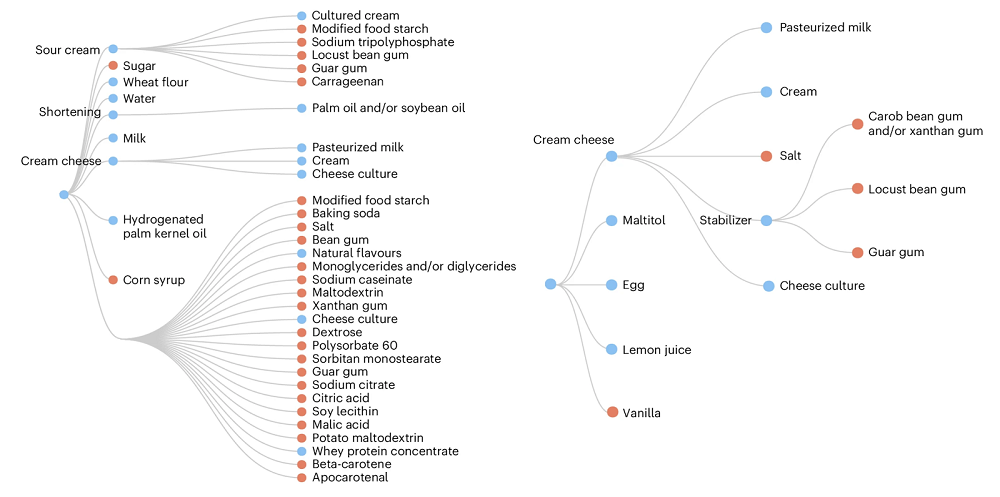

To illustrate the makeup of the FPro score for every product in GroceryDB, its ingredients are presented as a tree. This allows accounting for “ingredients of ingredients,” such as in this example with two cheesecakes. While both are highly processed, the one on the left has an FPro of 0.953 and the one on the right – 0.720. The former, along with many additives, contains sour cream which, in turn, contains a number of ingredients, such as modified food starch.

The highly processed ingredients are designated by red dots. The researchers mention, however, that this does not necessarily mean they are harmful. For example, xanthan gum, guar gum, and locust bean gum are considered generally safe. The purpose of GroceryDB is to allow people to dig into the ingredients of pantry staples and make informed decisions.

Informing the public’s choices

“GroceryDB serves as a proof of concept, demonstrating the potential of accessible, algorithm-ready data to advance nutrition research,” said Dr. Giulia Menichetti, a Principal Investigator and Junior Faculty at Harvard Medical School, and a co-author of the study. “This is especially significant in a field where much of the work still depends on labor-intensive manual curation, relying on descriptive definitions that suffer from poor inter-rater reliability and lack of reproducibility.”

“While the general population is increasingly aware of the potential health impacts of ultra-processed foods, they lack the knowledge to distinguish minimally processed foods, which have no known health consequences, from ultra-processed ones,” said Prof. Barabási. “Here, we set out to offer this resource by measuring the degree of processing for the foods that constitute a significant fraction of the US food supply. Most importantly, through this online resource, consumers are empowered to replace the ultra-processed foods they consume with brands that are less processed.”

Menichetti, too, underscored the potential societal benefits of their project. “Our vision with GroceryDB is not just to build a database, but to catalyze a global effort toward open-access, internationally comparable data that advances nutrition security and ensures equitable access to healthier food options for all,” she said.

Another nutrition scientist, Barry M. Popkin, Distinguished Professor of Nutrition at the University of North Carolina, who was not involved in this study, voiced some critique regarding its design: “Rather than doing an exact study of the ingredients list to find those colors, flavors and other additives identified in NOVA as identifying ultra-processed food, they guess on a set of foods that they were ultra-processed and then the machine identified the other ultra-processed foods.”

However, according to Menichetti, the approach suggested by Popkin “is not currently practical from an algorithmic perspective, due to the poor standardization of ingredient lists worldwide and the absence of definitions tied to robust, measurable variables across food composition databases.”

“Implementing such an approach,” she noted, “would have required significant manual curation, more than double the funding and time, and the incorporation of subjective opinions into the classification process. We see these challenges firsthand with our friends at Open Food Facts, a non-profit initiative powered by thousands of volunteers globally, which grapples with these same limitations daily.”

Literature

[1] Ravandi, B., Ispirova, G., Sebek, M., Mehler, P., Barabási, A. L., & Menichetti, G. (2025). Prevalence of processed foods in major US grocery stores. Nature Food, 1-13.

[2] Fiolet, T., Srour, B., Sellem, L., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Méjean, C., … & Touvier, M. (2018). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. bmj, 360.

[3] Srour, B., Fezeu, L. K., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Méjean, C., Andrianasolo, R. M., … & Touvier, M. (2019). Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). bmj, 365.

[4] Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., … & Zhou, M. (2019). Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell metabolism, 30(1), 67-77.