In a new study, researchers report producing self-assembling nanotubes and rings made from RNA molecules inside artificial cell-like lipid vesicles. In the future, this technology could facilitate the creation of synthetic cells for various research, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications [1].

Paperless origami

DNA and RNA molecules are central to life, carrying essential genetic information for protein production. However, their unique properties also make them excellent building materials. Nature discovered this eons ago; ribosomes, for instance, are partly built from RNA.

Scientists have experimented extensively with designing DNA and RNA sequences that cause molecules to self-assemble into predetermined shapes. The technique has become known under the poetic name “DNA (or RNA) origami” [2].

These engineered structures can be impressively intricate: for example, DNA “boxes” that carry drug molecules directly to target sites, then each open a molecular “door” to release their contents [3]. A new study from Heidelberg University, published in Nature Nanotechnology, takes RNA origami to the next level.

Tubes, rings, and networks

The researchers designed RNA molecules to self-assemble into structures resembling cellular cytoskeletons. The cytoskeleton, naturally composed of protein filaments and microtubules, is critical for maintaining cell shape and stability. “We designed RNA origami tiles that fold upon transcription and self-assemble into micrometer-long, three-dimensional RNA origami nanotubes,” the authors explain. Creating an artificial cytoskeleton is an important milestone on the path toward synthetic cells.

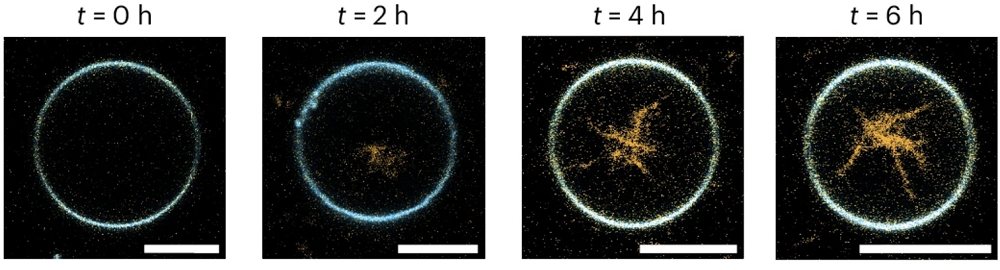

The team encapsulated DNA templates and RNA polymerase, the enzyme needed to transcribe DNA into RNA, into giant unilamellar lipid vesicles (GUVs), effectively creating proto-cells. To supply these synthetic cells with RNA building blocks (nucleotides), they used the bacterial transmembrane pore protein α-haemolysin. Magnesium ions (Mg2+) served as a trigger to prevent premature transcription, and the pore protein facilitated the removal of transcription byproducts.

When transcription was initiated, RNA strands immediately folded and assembled into nanotubes inside these synthetic cells. Remarkably, some nanotubes reached several micrometers in length, comparable to actual cellular cytoskeletal structures.

The researchers observed that subtle variations in the DNA template sequence significantly altered the RNA origami structures, demonstrating the method’s flexibility and ease of control. For instance, slight modifications switched the resulting structure from nanotubes to rings.

To scale up their creations, the researchers included aptamers: RNA sequences capable of binding to specific molecular targets, including other RNA molecules. With aptamers incorporated, the nanotubes formed “cytoskeleton-like networks tens of micrometers across.”

Aptamers also proved useful in creating cortex-like structures adhering to the lipid membrane, mirroring the cortices seen in real cells. Whether aptamers were used or not, a prolonged nucleotide supply led to structural networks becoming so extensive that they physically deformed the GUVs. Being able to maintain and alter the cell’s shape is another hallmark of a true cytoskeleton.

Possible applications

A major advantage of RNA origami is that these structures can be produced directly inside cells. Once DNA templates are introduced into cells, a single enzyme, T7 polymerase, can create numerous RNA products from these templates. In comparison, the full biological transcription-translation machinery requires over 150 genes.

“In contrast to DNA origami, RNA origami enables synthetic cells to manufacture their building blocks by themselves,” explained Dr. Kerstin Göpfrich, the study’s lead author, whose team, “Biophysical Engineering of Life,” conducts research at the Center for Molecular Biology of Heidelberg University (ZMBH). “This could open new perspectives on the directed evolution of such cells.”

This early-stage discovery has broad implications, including in aging research. It could help scientists better understand early cellular evolution, develop biomimetic systems, and engineer cells designed for specific tasks.

While creating fully functional synthetic eukaryotic cells remains distant due to their enormous complexity, the pathway toward viable, simplified prokaryotic “proto-cells” with limited but useful functions has just become shorter. Currently, bacteria are used extensively to produce biological molecules. However, minimal synthetic cells might simplify this process and even enable protein production directly within living organisms, circumventing bacterial immunogenicity issues.

Such proto-cells could, for example, produce essential proteins like collagen and elastin to maintain youthful extracellular matrix (ECM) function. Additionally, RNA origami structures could be introduced into existing cells to provide structural support and other functionalities.

The authors anticipate that future RNA origami structures will become more than passive scaffolds; they will actively perform complex cellular tasks by integrating ribozymes, RNA molecules capable of enzymatic activity. According to Göpfrich, the long-term research goal is the creation of fully functional molecular machinery for RNA-based synthetic cells.

Literature

[1] Tran, M. P., Chakraborty, T., Poppleton, E., Monari, L., Illig, M., Giessler, F., & Göpfrich, K. (2025). Genetic encoding and expression of RNA origami cytoskeletons in synthetic cells. Nature Nanotechnology, 1 – 8.

[2] Dey, S., Fan, C., Gothelf, K. V., Li, J., Lin, C., Liu, L., … & Zhan, P. (2021). DNA origami. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 1(1), 13.

[3] Udomprasert, A., & Kangsamaksin, T. (2017). DNA origami applications in cancer therapy. Cancer science, 108(8), 1535-1543.

View the article at lifespan.io