I’ve been interested in using trehalose by one means or another. I just discovered though that low amounts of trehalose can feed a dangerously virulent strain of clostridium difficile.

The consequences of clostridium difficile infection range from ongoing daily diarrhea to death. Those who must take a PPI to suppress stomach acid, such as myself (I have explored all of the alternatives and none is feasible) are prone to c.d. population growth. In my case I came down with weeks-long diarrhea. My integrated M.D. offered several simple remedies and all failed. The stool sample sent for culture came back and showed incredibly high population of c.d. We knocked it down with antibiotics and then probiotics plus saccharomyces boulardii. That was the only remedy that worked to end two months of the runs. I speculate that anyone who must take acid suppressors may have a high c.d. population and that oral or rectal administration of trehalose could be a risk.

I emphasize that this is speculation and that I do not presume to tell anyone to take trehalose or not. Just alerting to a possibility that deserves further inquiry.

There are 450,000 c.d. infections per annum in the U.S. and 29,000 deaths.

https://en.wikipedia...icile_infection

Journalistic account: https://jamanetwork....bstract/2675907

The strains belong to 2 C difficile ribotypes, RT027 and RT078. Infections from C difficile had always caused diarrhea and colitis, sometimes leading to surgery and even death. But starting around 2000, as the previously rare ribotype RT027 spread, the infections became more common, more severe, more resistant to treatment, more likely to relapse, and more deadly.

Between 2001 and 2010, the US rate of C difficile hospitalizations per 1000 adult discharges roughly doubled from 5.6 to 11.5. In 2011, C difficile caused almost half a million infections and approximately 15 000 deaths. That year, RT027 was associated with around a third of health care–associated C difficile infections.

Antibiotic resistance alone doesn’t fully explain the trends. Although RT027 strains are resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics, so are other nonepidemic ribotypes. So what was giving this particular brand of C difficile its edge?

In 2014, Britton demonstrated that epidemic RT027 strains outcompete other nonepidemic C difficile strains in human fecal bioreactors and mouse models. But the mechanism behind their advantage was still unknown.

In their recent Nature study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, Britton and collaborators looked at how an epidemic strain of RT027 responds to around 200 food sources—sugars and sugar alcohols, amino acids, and proteins—found in the large intestine, where C difficile causes disease. One food source in particular—trehalose—stood out as increasing growth 5-fold compared with a non-RT027 strain.

The researchers then supplemented 21 strains from 9 C difficile ribotypes commonly found in the clinical setting with either glucose or trehalose alone. Most of the strains grew on low amounts of glucose, but only epidemic strains of RT027 and another outbreak-associated ribotype, RT078, grew on low amounts of trehalose.

“That was a smoking gun for us,” Britton said.

Microbial genetics and physiology experiments further revealed that the 2 epidemic ribotypes have different mutations that allow them to metabolize low levels of trehalose.

In RT027-infected mice fed trehalose, amounts sufficient to promote growth of the epidemic strains survived the trip to the cecum, the pouch that connects the small and large intestines. The researchers also exposed RT027 strains to fluid samples from the small intestines of people eating their normal diets. Two out of 3 fluid samples strongly induced expression of the treA gene, which is required to metabolize trehalose, in RT027 strains. The findings suggest there may be enough trehalose in our diets for RT027 to live on.

https://www.nature.c...les/nature25178

Dietary trehalose enhances virulence of epidemic Clostridium difficile

Nature volume 553, pages 291–294 (18 January 2018) |

Abstract

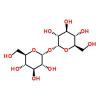

Clostridium difficile disease has recently increased to become a dominant nosocomial pathogen in North America and Europe, although little is known about what has driven this emergence. Here we show that two epidemic ribotypes (RT027 and RT078) have acquired unique mechanisms to metabolize low concentrations of the disaccharide trehalose. RT027 strains contain a single point mutation in the trehalose repressor that increases the sensitivity of this ribotype to trehalose by more than 500-fold. Furthermore, dietary trehalose increases the virulence of a RT027 strain in a mouse model of infection. RT078 strains acquired a cluster of four genes involved in trehalose metabolism, including a PTS permease that is both necessary and sufficient for growth on low concentrations of trehalose. We propose that the implementation of trehalose as a food additive into the human diet, shortly before the emergence of these two epidemic lineages, helped select for their emergence and contributed to hypervirulence.